Research and Publications

View article.

More frequent, larger, and severe wildfires necessitate greater resources for fire-prevention, fire-suppression, and postfire restoration activities, while decreasing critical ecosystem services, economic and recreational opportunities, and cultural traditions. Increased flexibility and better prioritization of management activities based on ecological needs, including commitment to long-term prefire and postfire management, are needed to achieve notable reductions in uncharacteristic wildfire activity and associated negative impacts. Collaboration and partnerships across jurisdictional boundaries, agencies, and disciplines can improve consistency in sagebrush-management approaches and thereby contribute to this effort. Here, we provide a synthesis on sagebrush wildfire trends and the impacts of uncharacteristic fire regimes on sagebrush plant communities, dependent wildlife species, fire-suppression costs, and ecosystem services. We also provide an overview of wildland fire coordination efforts among federal, state, and tribal entities.

View report.

The 2020 Resources Planning Act (RPA) Assessment summarizes findings about the status, trends, and projected future of the Nation’s forests and rangelands and the renewable resources that they provide. The 2020 RPA Assessment specifically focuses on the effects of both socioeconomic and climatic change on the U.S. land base, disturbance, forests, forest product markets, rangelands, water, biodiversity, and outdoor recreation. Differing assumptions about population and economic growth, land use change, and global climate change from 2020 to 2070 largely influence the outlook for U.S. renewable resources. Many of the key themes from the 2010 RPA Assessment cycle remain relevant, although new data and technologies allow for deeper and wider investigation. Land development will continue to threaten the integrity of forest and rangeland ecosystems. In addition, the combination and interaction of socioeconomic change, climate change, and the associated shifts in disturbances will strain natural resources and lead to increasing management and resource allocation challenges. At the same time, land management and adoption of conservation measures can reduce pressure on natural resources. The RPA Assessment findings and associated data can be useful to resource managers and policymakers as they develop strategies to sustain natural resources.

View article.

By connecting high-resolution estimates of fine fuel to climatic, biophysical and land-use factors, wildfire exposure, and a natural resource value at risk, we provide a pro-active and adaptive framework for fire risk management within highly variable and rapidly changing dryland landscapes.

View brief.

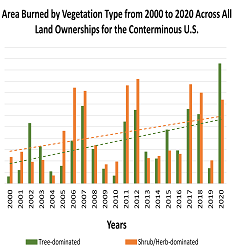

Wildfires burned more area on non-forested lands than forested lands over the past 20 years. This was true for all land ownerships in CONUS and the western US. Burned area increased over the 20-year time period for both non-forest and forest. Across CONUS, annual area burned was higher on non-forest than forests for 14 of the past 21 years (Fig. 1), and total area burned was almost 3,000,000 ha more in non-forest than in forest. For the western US, total burned area was almost 1,500,000 ha more in non-forest than in forest. From a federal agency perspective, approximately 74% of the burned area on Department of the Interior (DOI) lands occurred in non-forest and 78% of the burned area on US Forest Service (FS) lands occurred in the forest.

View synthesis.

We synthesized restoration techniques and their effectiveness in the Mojave and western Sonoran Desert, provide estimated costs of candidate techniques, and anticipate future research needs for effective restoration in changing climates and environments. Over 50 published studies in the Mojave and western Sonoran Desert demonstrate that restoration can improve soil features (e.g., biocrusts), increase cover of native perennial and annual plants, enhance native seed retention and seed banks, and reduce risk of fires to conserve mature shrubland habitat. We placed restoration techniques into three categories: restoration of site environments, revegetation, and management actions to limit further disturbance and encourage recovery. Within these categories, 11 major restoration techniques (and their variations) were evaluated by at least one published study and range from geomorphic (e.g., reestablishing natural topographic patterns) and abiotic structural treatments (e.g., vertical mulching) to active revegetation (e.g., outplanting, seeding).

View article.

Our systematic review returned a sample of 222 publications that met these criteria, with an increase in wilderness fire science over time. Studies largely occurred in the USA and were concentrated in a relatively small number of protected areas, particularly in the Northern Rocky Mountains. As a result, this sample of wilderness fire science is highly skewed toward areas of temperate mixed-conifer forests and historical mixed-severity fire regimes. Common principal subjects of publications included fire effects (44%), wilderness fire management (18%), or fire regimes (17%), and studies tended to focus on vegetation, disturbance, or wilderness management as response variables.

View article.

The West Coast both experiences the largest smoke exposures and contributes most to the burden of smoke PM2.5 in the western US. Applying prescribed burns on the coast yields large benefits for the West, while doing so in other states has relatively smaller impacts. Larger prescribed burns may reduce smoke impacts from future large wildfires, but few such burns have occurred in key areas.

View article.

We use a unique dataset derived from contemporary (∼2016) remeasurement of 440 historical quadrats (∼4m2) in the central Sierra Nevada, California, in which overstory trees, tree regeneration, and microsite conditions were measured and mapped both before and after logging in 1928–1929. Pine relative abundance changed little with logging and declined to 5% of the contemporary regeneration layer. In contrast, the relative abundance of incense-cedar regeneration (32%) already outpaced its representation in the overstory (17% by basal area) before logging and proceeded to dominate the contemporary understory (49%). We did not find strong evidence for the positive influence of gaps on pine regeneration in any time period. However, across species, post-logging skid trails were positively associated with regeneration and woody debris was negatively associated with regeneration in at least one time period. We discovered that the occurrence of advance regeneration (regeneration that preceded and survived logging) best predicted new contemporary trees across all species. For shade-tolerant species, post-logging regeneration that established up to ten years after logging was also associated with new contemporary trees. In contrast, the few pine that transitioned into the contemporary canopy during the study period all established prior to logging. Our work provides evidence that low pine abundance in the regeneration layer as early as 1928 contributed to low rates of pine in the overstory in 2016, showcasing that the decline of pine likely began before logging and official federal fire suppression policies. We suggest that fire exclusion before logging perpetuated shifts towards shade-tolerant and fire-intolerant species in the regeneration layer that were early and lasting.

View article.

Here, we present a detailed characterization of REBURN — a geospatial modeling framework designed to simulate reburn dynamics over large areas and long time frames. We interpret fire-vegetation dynamics for a large testbed landscape in eastern Washington State, USA. The landscape is comprised of common temperate forest and nonforest vegetation types distributed along broad topo-edaphic gradients. Each pixel in a vegetation type is represented by a pathway group (PWG), which assigns a specific state-transition model (STM) based on that pixel’s biophysical setting. STMs represent daily simulated and annually summarized vegetation and fuel succession, and wildfire effects on forest and nonforest succession. Wildfire dynamics are driven by annual ignitions, fire weather and topographic conditions, and annual vegetation and fuel successional states of burned and unburned pixels.