Article / Book

View article.

We found that within the sagebrush biome, fuel breaks are generally located in areas with high burn probability and are thus positioned well to intercept potential wildfires. However, fuel breaks are also frequently positioned in areas with lower predicted fuel break effectiveness relative to the sagebrush biome overall. Fuel breaks also are spatially associated with high invasive grass cover, indicating the need to better understand the causal relationship between fuel breaks and annual invasive grasses. We also show that the fuel break network is dense within priority wildlife habitats. Dense fuel breaks within wildlife habitats may trade off wildfire protection for decreased integrity of such habitats.

View article and brief.

Fire is strongly linked to outdoor recreation in the United States. Recreational uses of fires, whether in designated campgrounds or the backcountry, include warmth, cooking, and fostering a comfortable atmosphere. However, through inattention, negligence, or bad luck, recreational fires sometimes ignite wildfires. This paper evaluates whether the density of wildfire ignited by recreation or ceremony on U.S. Forest Service lands, and the size of such wildfires, is influenced by proximity to designated campgrounds, visitor density, previous and current drought conditions, and the type of vegetation surrounding the ignition point.

View article.

This paper uses qualitative data from a long-term ethnographic research project. Data include detailed fieldnotes, semi-structured interviews, and agency documents, which were systematically coded and thematically analyzed. In addition to the triggering effects of fatality incidents and agency initiatives to change organizational culture, external factors also directly impact the development of firefighter safety policies and practices. These include sociodemographic, material, political, and social-environmental factors. Identifying and understanding the influence of multi-scalar external factors on firefighter safety is essential to improving safety outcomes and reducing firefighters’ exposure to hazards.

View article and brief.

Although fuels treatments are generally shown to be effective at reducing fire severity, there is widespread interest in monitoring that efficacy as the climate continues to warm and the incidence of extreme fire weather increases. This paper compared basal area mortality across adjacent treated and untreated sites in the 2021 Dixie Fire of California’s Sierra Nevada.

View article.

This study defines five metrics that collectively provide comprehensive and complementary insights into the effect of fire regimes on ecosystem resilience and components of biodiversity. These include (1) Species Habitat Availability, a measure of the amount of suitable habitat for individual species; (2) Fire Indicator Species Index, population trends for species with clear fire responses; (3) Vegetation Resilience, a measure of plant maturity and the capability of vegetation communities to regenerate after fire; (4) Desirable Mix of Growth Stages, an indicator of the composition of post-fire age-classes across the landscape; and (5) Extent of High Severity Fire, a measure of the effect of severe fire on post-fire recovery of treed vegetation communities. Each metric can be quantified at multiple spatial and temporal scales relevant to evaluating fire management outcomes. Results highlight four characteristics of metrics that enhance their value for management: (1) they quantify both status and trends through time; (2) they are scalable and can be applied consistently across management levels (from individual reserves to the whole state); (3) most can be mapped, essential for identifying where and when to implement fire management; and (4) their complementarity provides unique insights to guide fire management for ecological outcomes.

View article.

This study aimed to determine the flammability of cheatgrass compared to two native perennial grasses (Columbia needlegrass [Achnatherum nelsonii] and bluebunch wheatgrass [Pseudoroegneria spicata]) across a range of fuel moistures. All three grass species had decreased flammability with increasing fuel moisture. Columbia needlegrass averaged 11% lower mass consumption than cheatgrass, and bluebunch wheatgrass had longer flaming duration and higher maximum temperatures than cheatgrass and Columbia needlegrass. The addition of cheatgrass to each perennial grass increased combined mass consumption, flaming duration, and flame heights. For these three attributes, the impact differed by the amount of cheatgrass in the mixture. Maximum and mean temperatures during perennial grass combustion were similar with and without cheatgrass addition. Some attributes of Columbia needlegrass flammability when burned with cheatgrass were higher than expected based on the flammability of each species, suggesting that Columbia needlegrass may be susceptible to pre-heating from combustion of cheatgrass. Conversely, the flammability of bluebunch wheatgrass and cheatgrass together had both positive and negative interactive effects, suggesting the impact on joint flammability from cheatgrass differs by perennial grass species.

View article.

View story map.

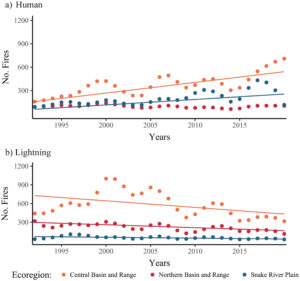

This study estimates how fire regimes have changed in the major Great Basin vegetation types over the past 60 years with comparisons to historical (pre-1900) fire regimes. We explore potential drivers of fire regime changes using existing spatial data and analysis. Across vegetation types, wildfires were larger and more frequent in the contemporary period (1991–2020) than in the recent past (1961–1990). Contemporary fires were more frequent than historical in two of three ecoregions for the most widespread vegetation type, basin and Wyoming big sagebrush. Increases in fire frequency also occurred in saltbush, greasewood, and blackbrush shrublands, although current fire return intervals remain on the order of centuries. Persistent juniper and pinyon pine woodlands burned more frequently in contemporary times than in historical times. Fire frequency was relatively unchanged in mixed dwarf sagebrush shrublands, suggesting they remain fuel-limited. Results suggest that quaking aspen woodlands may be burning less frequently now than historically, but more frequently in the contemporary period than in the recent past. We found that increased fire occurrence in the Great Basin is associated with increased abundance and extent of nonnative annual grasses and areas with high concentrations of anthropogenic ignitions. Findings support the need for continuing efforts to reduce fire occurrences in Great Basin plant communities experiencing excess fire and to implement treatments in communities experiencing fire deficits. Results underscore the importance of anthropogenic ignitions and discuss more targeted education and prevention efforts. Knowledge about signals of fire regime changes across the region can support effective deployment of resources to protect or restore plant communities and human values.

View booklet.

The reciprocal nature of our human interactions with our natural environment can be viewed through the lens of fire management in the West by federal, state, and private land managers. A wildfire’s impact is not affected by the presence of a geopolitical boundary, it is still inherently a natural process fueled by relatively well-understood dynamics. Yet, changing climate conditions such as extended heat waves, droughts, shifts in rainfall patterns or types of precipitation are changing how fire behaves in the West. From a Tribal member’s perspective, these climatic conditions, social development, and ecological degradation are all connected events with relatively predictable consequences. Because there is a reciprocal relationship with our environment, we are collectively accountable for the consequences of our choices in a modern context through a changing climate.

View article.

We sampled depth-resolved layers from fire-impacted soil and combusted litter and woody materials in a series of recent pile burn scars near West Yellowstone, Montana and nearby unburned mineral soil controls to assess whether the pile burn scars exhibited microbial signatures characteristic of forest soils impacted by recent high severity wildfire. Changes in soil carbon and nitrogen chemistry and patterns of microbial alpha and beta diversity broadly aligned with those observed following wildfire, particularly the enrichment of so-called ‘pyrophilous’ taxa. Furthermore, many of the taxa enriched in burned soils likely encoded putative traits that benefit microorganisms colonizing these environments, such as the potential for fast growth or utilization of pyrogenic carbon substrates. We suggest that pile burn scars may represent a useful proxy along the experimental gradient from muffle furnace or pyrocosm studies to largescale prescribed burns in the field to advance understanding of the soil (and related layers, like ash) microbiome following high severity wildfires, particularly when coupled with experimental manipulation. Finally, we discuss existing research gaps that experimentally manipulated pile burns could be utilized to address.

View article.

Strategic development and implementation of burn boss training may increase the likelihood that burn bosses can safely and effectively implement prescribed burns. This article presents a case study for applying key adult learning methods to improve training effectiveness that can be applied to other training topics in and outside wildland fire management.